The Persian cat (Persian: گربه ایرانی, romanized: Gorbe Īrānī) is a long-haired breed of cat characterized by its round face and short muzzle. It is also known as the "Persian Longhair" in the English-speaking countries. In the Middle East region, they are widely known as "Iranian cat" and in Iran they are known as "Shiraz cat". The first documented ancestors of the Persian were imported into Italy from Iran (historically known as Persia in the west) around 1620.[1][2] Recognized by the cat fancy since the late 19th century, it was developed first by the English, and then mainly by American breeders after the Second World War. Some cat fancier organizations' breed standards subsume the Himalayan and Exotic Shorthair as variants of this breed, while others treat them as separate breeds.

The selective breeding carried out by breeders has allowed the development of a wide variety of coat colors, but has also led to the creation of increasingly flat-faced Persians. Favored by fanciers, this head structure can bring with it a number of health problems. As is the case with the Siamese breed, there have been efforts by some breeders to preserve the older type of cat, the traditional breed, having a more pronounced muzzle, which is more popular with the general public. Hereditary polycystic kidney disease is prevalent in the breed, affecting almost half the population in some countries.[3][4]

In 2015 it was ranked as the 2nd most popular breed in the United States according to the Cat Fanciers' Association.[5] The first is the Exotic breed.

Contents

Origin[edit]

It is not clear when long-haired cats first appeared, as there are no known long-haired specimens of the African wildcat, the ancestor of the domestic subspecies.

The first documented ancestors of the Persian were imported from Khorasan, Iran, into Italy in 1620 by Pietro della Valle, and from Angora (now Ankara), Ottoman Empire (Turkey), into France by Nicholas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc at around the same time. The Khorasan cats were grey coated while those from Angora were white. From France, they soon reached Britain.[6][self-published source]

Recent genetic research indicates that present day Persians are related not to cats from the Near East but to cats from Western Europe. The researchers stated, "Even though the early Persian cat may have in fact originated from Persia (Iran), the modern Persian cat has lost its phylogeographical signature."[7]

Development[edit]

Persians and Angoras[edit]

This section contains overly lengthy quotations for an encyclopedic entry. (December 2011)

|

The first Persian cat was presented at the first organized cat show, in 1871 in the Crystal Palace in London, England, organized by Harrison Weir. As specimens closer to the later established Persian conformation became the more popular types, attempts were made to differentiate it from the Angora.[8] The first breed standard (then called a points of excellence list) was issued in 1889 by cat show promoter Weir. He stated that the Persian differed from the Angora in the tail being longer, hair more full and coarse at the end and head larger, with less pointed ears.[9] Not all cat fanciers agreed with the distinction of the two types, and in the 1903 work The Book of the Cat, Francis Simpson states that "the distinctions, apparently with hardly any difference, between Angoras and Persians are of so fine a nature that I must be pardoned if I ignore the class of cat commonly called Angora".[10]

Dorothy Bevill Champion lays out the difference between the two types in the 1909 Everybody's Cat Book:[11]

Bell goes on to detail the differences. Persian coats consists of a woolly under coat and a long, hairy outer coat. The coat loses all the thick underwool in the summer, and only the long hair remains. Hair on the shoulders and upper part of the hind legs is somewhat shorter. Conversely, the Angora has a very different coat which consists of long, soft hair, hanging in locks, "inclining to a slight curl or wave on the under parts of the body." The Angora's hair is much longer on the shoulders and hind legs than the Persian, which Bell considered a great improvement. However, Bell says the Angora "fails to the Persian in head," Angoras having a more wedge-shaped head and Persians having a more appealing round head.

Bell notes that Angoras and Persians have been crossbred, resulting in a decided improvement to each breed, but claimed the long-haired cat of 1909 had significantly more Persian influence than Angora.

Champion lamented the lack of distinction among various long-haired types by English fanciers, who in 1887, decided to group them under the umbrella term "Long-haired Cats".[11][12]

Traditional Persian[edit]

The traditional Persian, or doll-face Persian,[13] are somewhat recent names for what is essentially the original breed of Persian cat, without the development of extreme features.

As many breeders in the United States, Germany, Italy, and other parts of the world started to interpret the Persian standard differently, they developed the flat-nosed "peke-face" or "ultra-type" over time, as the result of two genetic mutations, without changing the name of the breed from "Persian". Some organizations, including the Cat Fanciers' Association (CFA), today consider the peke-face type as their modern standard for the Persian breed. Thus the retronym Traditional Persian was created to refer to the original type, which is still bred today, mirroring the renaming of the original-style Siamese cat as the Traditional Siamese or Thai, to distinguish it from the long-faced modern development which has taken over as simply "the Siamese".

Not all cat fancier groups recognize the Traditional Persian (at all, or as distinct), or give it that specific name. TICA has a very general standard, that does not specify a flattened face.[14]

Peke-face and ultra-typing[edit]

In the late 1950s a spontaneous mutation in red and red tabby Persians gave rise to the "peke-faced" Persian, named after the flat-faced Pekingese dog. It was registered as a distinct breed in the CFA, but fell out of favor by the mid-1990s due to serious health issues; only 98 were registered between 1958 and 1995. Despite this, breeders took a liking to the look and started breeding towards the peke-face look. The over-accentuation of the breed's characteristics by selective breeding (called extreme- or ultra-typing) produced results similar to the peke-faced Persians. The term peke-face has been used to refer to the ultra-typed Persian but it is properly used only to refer to red and red tabby Persians bearing the mutation. Many fanciers and CFA judges considered the shift in look "a contribution to the breed."[6][15][16][17]

In 1958, breeder and author P. M. Soderberg wrote in Pedigree Cats, Their Varieties, breeding and Exhibition[17]

While the looks of the Persian changed, the Persian Breed Council's standard for the Persian had remained basically the same. The Persian breed standard is, by its nature, somewhat open-ended and focused on a rounded head, large, wide-spaced round eyes with the top of the nose leather placed no lower than the bottom of the eyes.[clarification needed] The standard calls for a short, cobby body with short, well-boned legs, a broad chest, and a round appearance, everything about the ideal Persian cat being "round". It was not until the late 1980s that standards were changed to limit the development of the extreme appearance.[citation needed] In 2004, the statement that muzzles should not be overly pronounced was added to the breed standard.[18] The standards were altered yet again in 2007, this time to reflect the flat face, and it now states that the forehead, nose, and chin should be in vertical alignment.[19]

In the UK, the standard was changed by the Governing Council of the Cat Fancy (GCCF) in the 1990s to disqualify Persians with the "upper edge of the nose leather above the lower edge of the eye" from Certificates or First Prizes in Kitten Open Classes.[20][21]

While ultra-typed cats do better in the show ring, the public seems to prefer the less extreme, older "doll-face" types.[6]

Variants[edit]

Himalayan[edit]

In 1950, the Siamese was crossed with the Persian to create a breed with the body type of the Persian but colorpoint pattern of the Siamese. It was named Himalayan, after other colorpoint animals such as the Himalayan rabbit. In the UK, the breed was recognized as the Colorpoint Longhair. The Himalayan stood as a separate breed in the US until 1984, when the CFA merged it with the Persian, to the objection of the breed councils of both breeds. Some Persian breeders were unhappy with the introduction of this crossbreed into their "pure" Persian lines.[22][23]

The CFA set up the registration for Himalayans in a way that breeders would be able to discern a Persian with Himalayan ancestry just by looking at the pedigree registration number. This was to make it easy for breeders who do not want Himalayan blood in their breeding lines to avoid individuals who, while not necessarily exhibiting the colorpoint pattern, may be carrying the point coloration gene recessively. Persians with Himalayan ancestry has registration numbers starting with 3 and are commonly referred to by breeders as colorpoint carriers (CPC) or 3000-series cats, although not all will actually carry the recessive gene. The Siamese is also the source for the chocolate and lilac color in solid Persians.[24][25]

Exotic Shorthair[edit]

The Persian was used as an outcross secretly by some American Shorthair (ASH) breeders in the late 1950s to "improve" their breed. The crossbreed look gained recognition in the show ring, but other breeders unhappy with the changes successfully pushed for new breed standards that would disqualify ASH that showed signs of crossbreeding.

One ASH breeder who saw the potential of the Persian/ASH cross proposed, and eventually managed, to get the CFA to recognize them as a new breed in 1966, under the name Exotic Shorthair. Regular outcrossing to the Persian has made present-day Exotic Shorthair similar to the Persian in every way, including temperament and conformation, with the exception of the short dense coat. It has even inherited much of the Persian's health problems. The easier to manage coat has made some label the Exotic Shorthair "the lazy person's Persian".

Because of the regular use of Persians as outcrosses, some Exotics may carry a copy of the recessive longhair gene. When two such cats mate, there is a one in four chance of each offspring being longhaired. Longhaired Exotics are not considered Persians by CFA, although The International Cat Association accepts them as Persians. Other associations register them as a separate Exotic Longhair breed.[26]

Toy and teacup sizes[edit]

A number of breeders produce small-stature Persian cats under a variety of names. The generic terms are "toy" and "teacup" Persians (terms borrowed from the dog fancy), but the individual lines are often called "palm-sized", "pocket", "mini" and "pixie", due to their relatively small size. Currently, they are not recognized as a separate breed by major registries and each breeder sets their own standards for size.[27] These terms are considered controversial or marketing ploys as cats do not have the genetic mutations that dogs possess to produce miniature versions of themselves as cats have a strong genetic buffering mechanism that keeps the genes from mutating. Unscrupulous breeders have resorted to harmful and repetitive inbreeding to obtain smaller cats resulting in genetically weaker cats often with severe health issues and shortened lifespans.[28][29]

Chinchilla Longhair and Sterling[edit]

In the US, there was an attempt to establish the silver Persian as a separate breed called the Sterling, but it was not accepted. Silver and golden Persians are recognized, as such, by CFA. In South Africa, the attempt to separate the breed was more successful; the Southern Africa Cat Council (SACC) registers cats with five generations of purebred Chinchilla as a Chinchilla Longhair. The Chinchilla Longhair has a slightly longer nose than the Persian, resulting in healthy breathing and less eye tearing. Its hair is translucent with only the tips carrying black pigment, a feature that gets lost when out-crossed to other colored Persians. Out-crossing also may result in losing nose and lip liner, which is a fault in the Chinchilla Longhair breed standard. One of the distinctions of this breed is the blue-green or green eye color only with kittens having blue or blue-purple eye color.[30]

Popularity[edit]

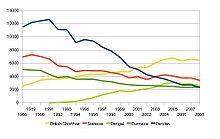

In 2008, the Persian was the most popular breed of pedigree cats in the United States.[31] In the UK, registration numbers have dwindled since the early 1990s and the Persian lost its top spot to the British Shorthair in 2001. As of 2012, it was the 6th most popular breed, behind the British Shorthair, Ragdoll, Siamese, Maine Coon and Burmese.[32] In France, the Persian is the only breed whose registration declined between 2003 and 2007, dropping by more than a quarter.[33]

The most color popular varieties, according to CFA registration data, are seal point, blue point, flame point and tortie point Himalayan, followed by black-white, shaded silvers and calico.[31]

Classification by registries[edit]

The breed standards of various cat fancier organizations may treat the Himalayan and Exotic Shorthair (or simply Exotic) as variants of the Persian, or as separate breeds. The Cat Fanciers' Association (CFA) treats the Himalayan as a color-pattern class of both the Persian and the Exotic, which have separate but nearly identical standards (differing in coat length).[34] The Fédération Internationale Féline (FIFe) entirely subsumes what other registries call the Himalayan as simply among the allowed coloration patterns for the Persian and the Exotic, treated as separate breeds.[35] The International Cat Association (TICA) treats them both as variants of the Persian.[14] The World Cat Federation (WCF) treats the Persian and Exotic Shorthair as separate breeds, and subsumes the Himalayan coloration as colorpoint varieties under each.[36]

Among regional and national organizations, Feline Federation Europe treats all three as separate breeds.[37] The American Cat Fanciers Association (ACFA) has the three as separate breeds (also with a Non-pointed Himalayan that is similar to the Persian).[38] The Australian Cat Federation (AFC) follows the FIFe practice.[39] The Canadian Cat Federation (CCA-AFC) treats the three separately, and even has an Exotic Longhair sub-breed of the Exotic and a Non-pointed Himalayan sub-breed of the Himalayan, which differ from the Persian only in having some mixed ancestry.[40] The (UK) Governing Council of the Cat Fancy (GCCF) does likewise.[21] treats the Persian and Exotic Shorthair as separate breeds covered by a single standard with a coat length distinction, and has the pattern of the Himalayan as simply a division within that standard.[41]

Characteristics[edit]

A show-style Persian has an extremely long and thick coat, short legs, a wide head with the ears set far apart, large eyes, and an extremely shortened muzzle. The breed was originally established with a short muzzle, but over time, this characteristic has become extremely exaggerated, particularly in North America. Persian cats can have virtually any color or markings.

The Persian is generally described as a quiet cat. Typically placid in nature, it adapts quite well to apartment life. Himalayans tend to be more active due to the influence of Siamese traits. In a study comparing cat owner perceptions of their cats, Persians rated higher than non-pedigree cats on closeness and affection to owners, friendliness towards strangers, cleanliness, predictability, vocalization, and fussiness over food.[42]

Coloration[edit]

The permissible colors in the breed, in most organizations' breed standards, encompass the entire range of cat coat-pattern variations.

The Cat Fanciers' Association (CFA), of the United States, groups the breed into four coat-pattern divisions, but differently: solid, silver and golden (including chinchilla and shaded variants, and blued subvariants), shaded and smoke (with several variations of each, and a third sub-categorization called shell), tabby (only classic, mackerel, and patched [spotted], in various colors), parti-color (in four classes, tortoiseshell, blue-cream, chocolate tortie, and lilac-cream, mixed with other colors), calico and bi-color (in around 40 variations, broadly classified as calico, dilute calico, and bi-color), and Himalayan (white-to-fawn body with point coloration on the head, tail and limbs, in various tints). CFA base colors are white, black, blue, red, cream, chocolate, and lilac. There are around 140 named CFA coat patterns for which the Himalayan qualifies, and 20 for the Himalayan sub-breed.[34] These coat patterns encompass virtually all of those recognized by CFA for cats generally. Any Persian permissible in TICA's more detailed system would probably be accepted in CFA's, simply with a more general name, though the organizations do not mix breed registries.

The International Cat Association (TICA) groups the breed into three coat-pattern divisions for judging at cat shows: traditional (with stable, rich colors), sepia ("paler and warmer than the traditional equivalents", and darkening a bit with age), and mink (much lighter than sepia, and developing noticeably with age on the face and extremities). If classified as the Himalayan sub-breed, full point coloration is required, the fourth TICA color division, with a "pale and creamy colored" body even lighter than mink, with intense coloration on the face an extremities. The four TICA categories are essentially a graduated scale of color distribution from evenly colored to mostly colored only at the points. Within each, the coloration may be further classified as solid, tortoiseshell (or "tortie"), tabby, silver or smoke, solid-and-white, tortoiseshell-and-white, tabby-and-white, or silver/smoke-and-white, with various specific colors and modifiers (e.g. chocolate tortoiseshell point, or fawn shaded mink marbled tabby-torbie). TICA-recognized tabby patterns include classic, mackerel, marbled, spotted, and ticked (in two genetic forms), while other patterns include shaded, chinchilla, and two tabbie-tortie variations, golden, and grizzled. Basic colors include white, black, brown, ruddy, bronze, "blue" (grey), chocolate, cinnamon, lilac, fawn, red, cream, with a silver or shaded variant of most. Not counting bi-color (piebald) or parti-color coats, nor combinations that are genetically impossible, there are nearly 1,000 named coat pattern variations in the TICA system for which the Persian/Himalayan qualifies. The Exotic Shorthair sub-breed qualifies for every cat coat variation that TICA recognizes.[14]

Eye colors range widely, and may include blue, copper, odd-eyed blue and copper, green, blue-green, and hazel. Various TICA and CFA coat categorizations come with specific eye-color requirements.[14][34]

Health[edit]

Pet insurance data from Sweden puts the median lifespan of cats from the Persian group (Persians, Chinchilla, Himalayan and Exotic) at just above 12.5 years. 76% of this group lived to 10 years or more and 52% lived to 12.5 years or more.[44] Veterinary clinic data from England shows an average lifespan of 12–17 years, with a median of 14.1.[45]

The modern brachycephalic Persian has a large rounded skull and shortened face and nose. This facial conformation makes the breed prone to breathing difficulties, skin and eye problems and birthing difficulties. Anatomical abnormalities associated with brachycephalic breeds can cause shortness of breath.[46] Malformed tear ducts causes epiphora, an overflow of tears onto the face, which is common but primarily cosmetic. It can be caused by other more serious conditions though. Entropion, the inward folding of the eyelids, causes the eyelashes to rub against the cornea, and can lead to tearing, pain, infection and cornea damage. Similarly, in upper eyelid trichiasis or nasal fold trichiasis, eyelashes/hair from the eyelid and hair from the nose fold near the eye grow in a way which rubs against the cornea.[47] Dystocia, an abnormal or difficult labor, is relatively common in Persians.[48] Consequently, stillbirth rate is higher than normal, ranging from 16.1% to 22.1%, and one 1973 study puts kitten mortality rate (including stillborns) at 29.2%.[49] A veterinary study in 2010 documented the serious health problems caused by the brachycephalic head.[50]

As a consequence of the BBC program Pedigree Dogs Exposed, cat breeders have also come under pressure from veterinary and animal welfare associations, with the Persian singled out as one of the breeds most affected by health problems.[51] Animal welfare proponents have suggested changes to breed standards to prevent diseases caused by over- or ultra-typing, and prohibiting the breeding of animals outside the set limits.[52] Apart from the GCCF standard that limits high noses, TICA[14] and FIFe standards require nostrils to be open, with FIFe stating that nostrils should allow "free and easy passage of air." Germany's Animal Welfare Act too prohibits the breeding of brachycephalic cats in which the tip of the nose is higher than the lower eyelids.[50]

Polycystic kidney disease (PKD) which causes kidney failure in affected adult cats has an incidence rate of 36–49% in the Persian breed.[53] The breed – and derived ones, like the British Longhair and Himalayan – are especially prone to autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD).[54] Cysts develop and grow in the kidney over time, replacing kidney tissues and enlarging the kidney. Kidney failure develops later in life, at an average age of 7 years old (ranging from 3 to 10 years old). Symptoms include excessive drinking and urination, reduced appetite, weight loss and depression.[55] The disease is autosomal dominant and DNA screening is the preferred method of eliminating the gene in the breed. Because of DNA testing, most responsible Persian breeders now have cats that no longer carry the PKD gene, hence their offspring also do not have the gene. Before DNA screening was available, ultrasound was done. However, an ultrasound is only as good as the day that it is done, and many cats that were thought to be clear, were in fact, a carrier of the PKD gene. Only DNA screening and then breeding negative to negative for the PKD gene will produce negative kittens which effectively removes this gene from the breeding pool has allowed some lines and catteries to eliminate the incidence of the disease.[56]

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a common heart disease in all cats. It is hereditary in the Maine Coon and American Shorthair, and likely the Persian. The disease causes thickening of the left heart chamber, which can in some instances lead to sudden death. It tends to affect males and mid- to old-aged individuals. Reported incidence rate in Persians is 6.5%.[57] Unlike PKD, which can be detected even in very young cats, heart tests for HCM have to be done regularly in order to effective track and/or remove affected individuals and their offspring from the breeding pool.[58]

The age at the first cardiac event was significantly lower in Maine Coons (2.5 years) versus other breeds (7 years). In Sphynx, the age at the time of diagnosis was 3.5 years. Concerning sudden death solely, Maine Coon cats died younger than other breeds. No sudden deaths were reported in Chartreux and Persian cats in this study. Sudden death was observed in only three breeds—Maine Coon, Domestic Shorthair, and Sphynx. All cats surviving longer than 15 years of age were Domestic Shorthair, Persians, or Chartreux.[59][60]

Early onset progressive retinal atrophy is a degenerative eye disease, with an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance in the Persian.[61] Despite a belief among some breeders that the disease is limited to chocolate and Himalayan lines, there is no apparent link between coat color in Persians and the development of PRA.[62] Basal cell carcinoma is a skin cancer which shows most commonly as a growth on the head, back or upper chest. While often benign, rare cases of malignancy tends to occur in Persians.[63] Blue smoke Persians are predisposed to Chédiak-Higashi syndrome. White cats, including white Persians, are prone to deafness, especially those with blue eyes.[64] Persians are more prone to side effects of ringworm drug Griseofulvin.[65]

As with in dogs, hip dysplasia affects larger breeds, such as Maine Coons and Persians. But the small size of cats means that they tend not to be as affected by the condition.[63] Persians are susceptible to malocclusion (incorrect bite), which can affect their ability to grasp, hold and chew food.[63] Even without the condition the flat face of the Persian can make picking up food difficult, so much so that specially shaped kibble have been created by pet food companies to cater to the Persian.[66]

Other conditions which the Persian is predisposed to are listed below:[67]

- Dermatological – primary seborrhoea, idiopathic periocular crusting, dermatophytosis (ringworm),[68] Facial fold pyoderma, idiopathic facial dermatitis (a.k.a. dirty face syndrome), multiple epitrichial cysts (eyelids)

- Ocular – coloboma, lacrimal punctal aplasia, corneal sequestrum, congenital cataract

- Urinary – calcium oxalate urolithiasis (feline lower urinary tract disease)

- Reproductive – cryptorchidism

- Gastrointestinal – congenital portosystemic shunt,[69] congenital polycystic liver disease (associated with PKD)

- Cardiovascular – peritoneopericardial diaphragmatic hernia

- Immunological – systemic lupus erythematosus

- Neurological – alpha-mannosidosis

- Neoplastic – basal cell carcinoma, sebaceous gland tumours

- Excessive tearing

- Eye condition such as cherry eye

- Heat sensitivity

- Predisposition to ringworm, a fungal infection

Although these health issues are common, many Persians do not exhibit any of these problems.

Grooming[edit]

This section does not cite any sources. (March 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

Since Persian cats have long, dense fur that they cannot effectively keep clean, they need regular grooming to prevent matting. To keep their fur in its best condition, they must be brushed frequently. Some advocate for bathing the cats in water, although many Persians are fine cleaning themselves. An alternative is to shave the coat. Their eyes may require regular cleaning to prevent crust buildup and tear staining.

Persian cats in art[edit]

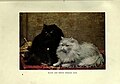

The art world and its patrons have long embraced their love for the Persian cat by immortalizing them in art. A 6-by-8.5-foot artwork that’s purported to be the “world’s largest cat painting” sold at auction for more than $820,000. The late 19th-century oil portrait is called My Wife's Lovers, and it once belonged to a wealthy philanthropist who commissioned an artist to paint her vast assortment of Turkish Angoras and Persians. Other popular Persian paintings include White Persian Cat by famous folk artist Warren Kimble and Two White Persian Cats Looking into a Goldfish Bowl by late feline portraitist Arthur Heyer. The beloved Persian cat has made its way onto the artwork of stamps around the world.[70][71][72][73]

References[edit]

- ^ "Persian Cat Information | Persian Cat Corner". Persian Cat Resource.

- ^ "Breed Profile: The Persian". www.cfa.org. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- ^ "Polycystic kidney disease | International Cat Care". icatcare.org. Retrieved July 8,2016.

- ^ "Polycystic Kidney Disease". www.vet.cornell.edu. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- ^ "Press Release February 1, 2016 - Top 10 Breeds for 2015". cfa.org. Retrieved July 8,2016.

- ^ a b c Hartwell, Sarah (2013). "Longhaired Cats". Messybeast Cats. Sarah Hartwell. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ^ Lipinski, Monika J.; Froenicke, Lutz; Baysac, Kathleen C.; Billings, Nicholas C.; Leutenegger, Christian M.; Levy, Alon M.; Longeri, Maria; Niini, Tirri; Ozpinar, Haydar; Slater, Margaret R.; Pedersen, Niels C.; Lyons, Leslie A. (January 2008). "The Ascent of Cat Breeds: Genetic Evaluations of Breeds and Worldwide Random Bred Populations". Genomics. 91 (1): 12–21. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.10.009. PMC 2267438. PMID 18060738.

- ^ Helgren, J. Anne. (2006). "Cat Breed Detail: Persian Cats". Iams.com. Telemark Productions / Procter & Gamble. Archived from the original on November 19, 2008. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ^ Weir, Harrison (1889). Our Cats and All About Them. Tunbridge Wells, UK: R. Clements & Co. LCCN 2002554760. OL 3664970M. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ^ Simpson, Frances. (1903). The Book of the Cat. London/New York: Cassell and Company. p. 98. LCCN 03024964. OL 7205700M. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ^ a b Champion, Dorothy Bevill (1909). Everybody's Cat Book. New York: Lent & Graff. p. 17. LCCN 10002159. OCLC 8291178. OL 7015748M. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ^ Helgren, J. Anne (2006). "Cat Breed Detail: Turkish Angora". Iams.com. Telemark Productions / Procter & Gamble. Archived from the original on May 9, 2010. Retrieved July 9, 2015.[unreliable source?]

- ^ "Cats and Kittens: Maine coon Kittens". Retrieved March 17, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "Persian Breed Group" (PDF). TICA.org. Harlingen, Texas: The International Cat Association. May 1, 2004. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ^ Saunders, Lorraine (November 2002). "Solid Color Persians Are...Solid As a Rock?". Cat Fanciers' Almanac. Cat Fanciers' Association. Archived from the original on December 1, 2010. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ^ Brocato, Judy; Brocato, Greg (March 1995). "Stargazing: A Historical View of Solid Color Persians". Cat Fanciers' Almanac. Cat Fanciers' Association. Archived from the originalon December 1, 2010. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ^ a b Hartwell, Sarah (2010). "Novelty Breeds and Ultra-Cats – A Breed Too Far?". Messybeast Cats. Retrieved July 9, 2015.[self-published source]

- ^ "2003 Breed Council Ballot Proposals and Results". CFA Persian Breed Council. 2004. Retrieved October 17, 2009.

- ^ "2006 Breed Council Ballot Proposals and Results". CFA Persian Breed Council. 2007. Retrieved October 17, 2009.

- ^ Bi-Color and Calico Persians: Past, Present and Future Archived August 27, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Cat Fanciers' Almanac. May 1998

- ^ a b "Persian Section" (PDF). GCCFCats.org. Governing Council of the Cat Fancy. 2015. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ^ Helgren, J. Anne. (2006). "Cat Breed Detail: Himalayan". Iams.com. Telemark Productions / Procter & Gamble. Archived from the original on November 19, 2008. Retrieved July 9, 2015.[unreliable source?]

- ^ Himalayan-Persian Archived September 13, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Cat Fanciers' Almanac May 1999

- ^ Breed Profile: Persian – Solid Color Division Archived September 17, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Cat Fanciers' Association

- ^ "CFA ANNUAL AND EXECUTIVE BOARD MEETINGS JUNE 23–27, 2004" (PDF). cfainc.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 13, 2010.

- ^ Helgren, J. Anne. (2006). "Cat Breed Detail: Exotic Shorthair". Iams.com. Telemark Productions / Procter & Gamble. Archived from the original on November 19, 2008. Retrieved July 9, 2015.[unreliable source?]

- ^ Hartwell, Sarah (2013). "Dwarf, Midget and Miniature Cats – Purebreds (Including 'Teacup Cats')". Messybeast Cats. Retrieved July 9, 2015.[self-published source]

- ^ "Breeding Cats and Dogs". indianapublicmedia.org.

- ^ "Think Twice Before you Buy A Teacup Persian Cat". kittentoob.com. November 25, 2014.

- ^ Difference Between Chinchilla Rodent and Chinchilla Cat Chinchillafactssite.com

- ^ a b 2008 Top Pedigreed Breeds Archived April 1, 2010, at the Wayback MachineCFA. March 2009.

- ^ "Analysis of Breeds Registered" (PDF). Governing Council of the Cat Fancy. 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 30, 2013. Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- ^ Javerzac, Anne-marie (2008). "Palmarès du chat de race en France: Les données 2008 du LOOF" (in French). ANIWA. Archived from the original on October 26, 2008.

- ^ a b c "Persian Show Standard" (PDF). CFAInc.com. Alliance, Ohio: Cat Fanciers' Association. 2015. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ^ "Category I: Exotic/Persian" (PDF). FIFeweb.org. Jevišovkou, Czech Republic: Fédération Internationale Féline. January 1, 2015. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ^ "Breed Standards: Persian–Colourpoint" (PDF). WCF-Online.de. Essen, Germany: World Cat Federation. January 1, 2010. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ^ "British Shorthair and Highlander". Bavarian-CFA.de. Feline Federation Europe. September 25, 2004. Archived from the original on July 11, 2015. Retrieved July 9, 2015.Note: Due to poor coding at this site, this link goes directly to the standard's content. To see it loaded in the site's navigation frame, go to http://www.ffe.europe.de[permanent dead link], and manually navigate to the breed's entry under the "Races Standard" menu item.

- ^ "Persian" (PDF). ACFACat.com. Nixa, Missouri: American Cat Fanciers' Association. May 2015. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ^ "ACF Standards: Persian [PER]" (PDF). Canning Vale, Western Au.: Australian Cat Federation. January 1, 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 1, 2015. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ^ "Persian" (PDF). CCA-AFC.com. Mississauga, Ontario: Canadian Cat Federation. August 6, 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 30, 2012. Retrieved July 9,2015. Also referred to corresponding Exotic Archived September 16, 2012, at the Wayback Machine and Himalayan Archived October 30, 2012, at the Wayback Machine standards.

- ^ "Breed's Standard: Persian & Exotic Shorthair". LOOF.asso.fr. Pantin, France: Livre Officiel des Origines Félines. 2015. Retrieved July 10, 2015.

- ^ Turner, D. C. (2000). "Human-cat interactions: relationships with, and breed differences between, non-pedigree, Persian and Siamese cats". In Podberscek, A. L.; Paul, E. S.; Serpell, J. A. (eds.). Companion Animals & Us: Exploring the Relationships Between People & Pets. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 257–271. ISBN 978-0-521-63113-6.

- ^ "Uniform Color Descriptions and Glossary of Terms" (PDF). The International Cat Association. January 1, 2015. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ^ a b Egenvall, A.; Nødtvedt, A.; Häggström, J.; Ström Holst, B.; Möller, L.; Bonnett, B. N. (2009). "Mortality of Life-Insured Swedish Cats during 1999—2006: Age, Breed, Sex, and Diagnosis". Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 23 (6): 1175–1183. doi:10.1111/j.1939-1676.2009.0396.x. PMID 19780926.

- ^ O'Neill, D. G. (2014). "Longevity and mortality of cats attending primary care veterinary practices in England". Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 17 (2): 125–33. doi:10.1177/1098612X14536176. PMID 24925771. "n=70, median=14.1, IQR 12.0-17.0, range 0.0-21.2"

- ^ Künzel, W.; Breit, S.; Oppel, M. (2003). "Morphometric Investigations of Breed-Specific Features in Feline Skulls and Considerations on their Functional Implications". Anatomia, Histologia, Embryologia: Journal of Veterinary Medicine Series C. 32 (4): 218–223. doi:10.1046/j.1439-0264.2003.00448.x. PMID 12919072.

- ^ Stades, Frans Cornelis; et al. (2007). Ophthalmology for the Veterinary Practitioner (2nd rev. and expanded ed.). Hannover: Schlütersche. ISBN 978-3-89993-011-5.

- ^ Gunn-Moore, D. A.; Thrusfield, M. V. (1995). "Feline dystocia: prevalence, and association with cranial conformation and breed". Vet Rec. 136 (14): 350–353. doi:10.1136/vr.136.14.350. PMID 7610538.

- ^ Susan Little Aspects of Reproduction and Kitten Mortality in the Devon Rex cat And a Review of the Literature Devon Rex Kitten Information Project

- ^ a b Schlueter, C.; Budras, K. D.; Ludewig, E.; Mayrhofer, E.; Koenig, H. E.; Walter, A.; Oechtering, G. U. (2009). "Brachycephalic feline noses: CT and anatomical study of the relationship between head conformation and the nasolacrimal drainage system" (PDF). Journal of Feline Medicine & Surgery. 11 (11): 891–900. doi:10.1016/j.jfms.2009.09.010. PMID 19857852.

- ^ Copping, Jasper (March 14, 2009). "Inbred pedigree cats suffering from life-threatening diseases and deformities". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved November 8, 2009.

- ^ Steiger, Andreas (2005). "Chapter 10: Breeding and Welfare". In Rochlitz, Irene (ed.). The Welfare of Cats. 3. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-6143-1.

- ^ "Polycystic Kidney Disease". Genetic welfare problems of companion animals. Universities Federation for Animal Welfare. Archived from the original on April 3, 2012. Retrieved August 4, 2012.

- ^ Bell, Jerold; Cavanagh, Kathleen; Tilley, Larry; Smith, Francis W. K. (2012). Veterinary Medical Guide to Dog and Cat Breeds. Teton NewMedia. pp. 558–559. ISBN 9781482241419.

- ^ Hosseininejad, M.; Vajhi, A.; Marjanmehr, H.; Hosseini, F. (2008). "Polycystic kidney in an adult Persian cat: Clinical, diagnostic imaging, pathologic, and clinical pathologic evaluations". Comparative Clinical Pathology. 18: 95–97. doi:10.1007/s00580-008-0744-0.

- ^ Lyons, Leslie. Polycystic Kidney Disease (PKD) Feline Genome Project

- ^ Norsworthy, Gary D.; Crystal, Mitchell A.; Fooshee Grace, Sharon; Tilley, Larry P. (2007). The Feline Patient. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-7817-6268-7.

- ^ Feline Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Advice for Breeders Archived May 13, 2008, at the Wayback Machine The Winn Feline Foundation

- ^ Trehiou-Sechi, E; Tissier, R; Gouni, V; Misbach, C; Petit, A. M.; Balouka, D; Sampedrano, C. C.; Castaignet, M; Pouchelon, J. L.; Chetboul, V (2012). "Comparative echocardiographic and clinical features of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in 5 breeds of cats: A retrospective analysis of 344 cases (2001-2011)". Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 26 (3): 532–41. doi:10.1111/j.1939-1676.2012.00906.x. PMID 22443341.

- ^ "Cat Health News from the Winn Feline Foundation". winnfelinehealth.blogspot.com.

- ^ Rah, H; Maggs, D. J.; Blankenship, T. N.; Narfstrom, K; Lyons, L. A. (2005). "Early-onset, autosomal recessive, progressive retinal atrophy in Persian cats". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 46 (5): 1742–7. doi:10.1167/iovs.04-1019. PMID 15851577.

- ^ Rah H, Maggs D, Lyons L (2006). "Lack of genetic association among coat colors, progressive retinal atrophy and polycystic kidney disease in Persian cats". J Feline Med Surg. 8 (5): 357–60. doi:10.1016/j.jfms.2006.04.002. PMID 16777456.

- ^ a b c Cat Owner's Home Veterinary Handbook

- ^ Strain, George M. Cat Breeds With Congenital Deafness

- ^ Griseofulvin (Fulvicin) VeterinaryPartner.com

- ^ Persian 30 Royal Canin

- ^ Gould, Alex; Thomas, Alison (2004). Breed Predispositions to Diseases in Dogs and Cats. Ames, Iowa: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-0748-8.

- ^ "Dermatophytosis". Genetic welfare problems of companion animals. Universities Federation for Animal Welfare. Archived from the original on March 11, 2014. Retrieved August 4, 2012.

- ^ "Portosystemic Shunt". Genetic welfare problems of companion animals. Universities Federation for Animal Welfare. Archived from the original on March 28, 2015. Retrieved August 4, 2012.

- ^ "Sotheby's Is Auctioning Off What Might Be the World's Largest Cat Painting". October 26, 2015. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

- ^ "Carl Kahler My Wife's Lovers Auction | Architectural Digest". Architectural Digest. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

- ^ "10 Fancy Facts About Persian Cats". November 20, 2015. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

- ^ "U.S. Postal Stamps Will Feature Cats In 2016". iHeartCats.com – Because Every Cat Matters ™. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

.png)

0 Comments:

Post a Comment